PGY-3 Family Practice Anaesthesia – University of British Columbia

ResidentSenior ResidentFamily Practice Anaesthesia University of British Columbia

November 2017

About Me

Hey there! My name is Theresa Lee, and I recently completed the PGY-3 year in family practice Anaesthesia (FPA) at the University of British Columbia.

I am originally from St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, where I obtained a Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Biochemistry, a Bachelor of Arts in French, my MD designation, and pursued rural family medicine training at Memorial University. Prior to my enhanced-skills year, I had a generalist practice in the eastern Arctic on Baffin Island, Nunavut, which included obstetrics, emergency medicine, and hospitalist work. I will return to Baffin as a full-time physician after a stint in the western Arctic in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, and after completing the Diploma in Tropical Medicine program at the London School of Hygiene in the UK.

I have long been interested in social justice, global health, and adventure – Northern rural medicine has been the perfect marriage of all these things. My undergraduate medical and residency trajectories have permitted me to explore numerous remote areas of our country. After a year of practice in a stunning yet austere Arctic environment with significant morbidity and acuity, I felt I needed further training in critical care. Coincidentally, the Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin) region also needed another family practice anaesthetist (FPA, or archaically, GPA), which was further impetus to apply. Returning to residency after being an independent practitioner was arduous for a myriad of reasons, but I have no regrets about having acquired extra knowledge and skills!

Clinical Life

What does a typical day of clinical duties involve?

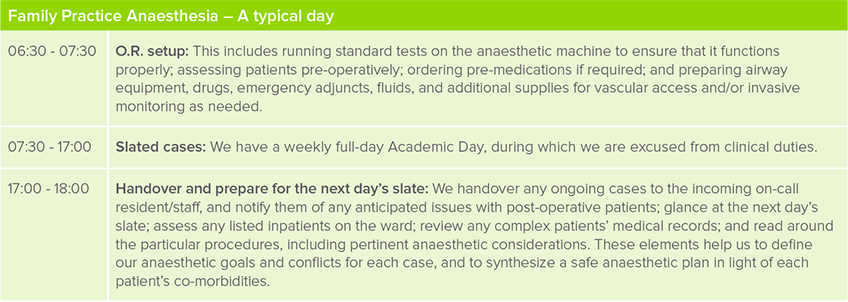

FPA residents are often grouped with the PGY-2 anaesthesiology cohort, and share the same atypical schedule as any anaesthesiology trainee. We participate in academic days and other educational opportunities, such as simulations and journal club meetings, alongside our Royal College colleagues.

What kinds of clinical rotations are required in your program?

The way the year is organized varies from province to province and program to program. At UBC, we are generously funded to attend the annual FPA bootcamp in Sudbury, Ontario, to jumpstart our year. Subsequently we do, in any order, one block of ICU, one elective block, and eleven blocks of Anaesthesia, including two in paediatrics, two in obstetrics, and a month of community FPA in Whitehorse, Yukon. Ideally, we start with general adult anesthesia, and end with paediatrics and the community FPA rotation (or a well-rounded general pool Anaesthesia rotation at a community hospital, such as Lions Gate) as we consolidate our knowledge and gain independence to transition to practice.

Which of your personality characteristics have been particularly helpful in your field?

Tenacity and humility. I will never know everything, but I can always try. I have enough insight to recognize whenever something is beyond my own capability, and when it is more appropriate to ask for assistance. This sixth sense has thus far kept me out of trouble.

What are the best aspects of your residency?

Anaesthesia may, in itself, be exciting, but I don’t really identify much with the field. For me, the most appealing characteristic of rural family medicine is the variety. Professionally, no two weeks look the same on my schedule. Although I like Anaesthesia and the bit of confidence with which my extra year of training has imbued me, I love primary care, and in particular, obstetrics. I love being able to participate in the comprehensive, longitudinal care of patients from the ED to the OR to the ward, and then to the clinic for follow-up. It is highly rewarding work.

What are the most challenging aspects of your residency?

Personally, I find the ungodly early morning starts the most difficult. (I jest … kind of.)

When we train as FPAs, we are primarily mentored by our specialist peers, who are acclimatized to tertiary care medicine at academic institutions brimming with resources, and who are sometimes unaware of the realities of practicing in resource-limited peripheral communities. One of the major challenges is learning to modify what we are taught in an urban environment to suit the context of a rural setting (that naturally has less access to drugs/equipment/people) while remaining safe practitioners. As Anaesthetists, we are risk-assessors and -mitigators; there is no room for blind heroics. Furthermore, we are primary care practitioners first and foremost, so we fulfill quite a different role in our respective communities.

Acquiring experiential CME (continuing medical education) can be difficult when we work in small, remote locales with lower volumes of certain clinical situations and procedures.

Finally, although Anaesthesiologists across the country serve as crisis leaders, we FPAs are often the only local critical care “experts” available in any given town—likely on-call every day for many weeks at a time, and likely to be summoned to help manage a broad spectrum of patients from neonates to the elderly—all of which can be exceptionally daunting if we happen to be providing single-physician coverage too.

What is one question you’re often asked about your residency?

It’s not a question, but unless they have trained in a fairly rural setting where FPAs are prevalent, learners are often surprised that our field exists at all. I certainly didn’t get any exposure to it as a career option during medical school, and really didn’t know much about it as a family medicine resident either.

Can you describe the transition from clerkship into residency?

No, as the details are now vague, but I can definitely describe the reverse-transition from staff to junior resident (at length, in private, over beverages)!

Will you be pursuing further training or looking for employment? What resources are available to you for future-planning?

Landing a rural medicine gig is usually as straightforward as following word-of-mouth leads and negotiating with regional health authority recruiters. As of writing this profile, I am nearing the end of a two-week stretch of 24/7 FPA call as a locum in Inuvik, NT, which has included daily O.R. or endoscopy slates, working 12-hour ED shifts (which can get a bit tangly when you are simultaneously on-call for Anaesthesia, and the nearest respiratory therapist is over 1000-km away by plane), seeing patients in family medicine clinic, and rounding on any inpatients whom I have admitted to our acute care ward.

After an upcoming educational detour in London, I will return to a full-time, full-scope family medicine practice with the additional provision of Anaesthesia services in Iqaluit, NU. I aim to learn as much Inuktitut as possible in order to be better equipped to provide culturally-appropriate care. I am also considering pursuing a master’s degree in public health via distance education—primarily to add more letters after my name, of course—and hopefully some international opportunities in the future.

Non-Clinical Life

What are your academic interests (e.g. leadership activities, research)?

I enjoy teaching trainees, and am a clinical assistant professor in the Discipline of Family Medicine at Memorial University of Newfoundland. Since Iqaluit is a training site for FPA residents at the University of Ottawa, there is the possibility of seeking a part-time faculty appointment there as well. I have a predilection for mentoring youth interested in health careers, and try to regularly engage in public speaking roles at schools. I am passionate about health advocacy for marginalized populations, which is the most salient reason why I chose to become a northern generalist.

What is your work-life balance like, and how do you achieve this?

Admittedly, my work-life balance was and is far better as a staff physician than it ever was as a resident! I love cooking, especially with and for other people, and that helps me maintain strong relationships with those who are most important to me.

Our FPA cohort created and consumed weekly Sunday dinners together throughout the year; it compensated for not having time to volunteer at a community soup kitchen like I normally do. I like climbing/bouldering, hiking/trekking, casual cycling (none of that touring-in-spandex stuff), surfing, hot yoga, and travel, and I intentionally carved out time for all these things regardless of how exhausted or overwhelmed I felt. Pushing through the unpleasantness of rising from a very comfortable nap is usually a worthwhile endeavour; however, sometimes, you just desperately need to sleep, and it’s entirely acceptable to admit that you’re only human!